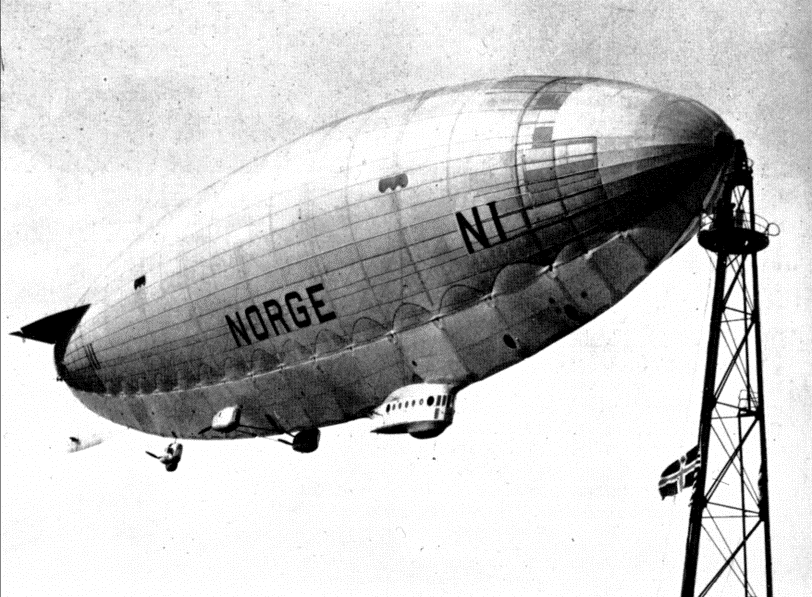

The airship NORGE

In comparison with other long-range airships of its time, the NORGE, the first one to have actually crossed the Arctic cap and to fly over the North Pole, was relatively small. Its total available power and range were modest. In order to safely conduct the flight from Svalbard to Alaska, the original structure of the airship had to be modified so as to spare weight. The initial, large and luxurious passenger and crew gondola was to be dismantled and replaced by a smaller one. The “walls” of the gondola were mostly made of fabric and window glass was substituted by celluloid film.

The structure

The NORGE was an airship of the semi-rigid type. Its envelope and gasbags were kept in shape by a longitudinal keel attached from the bow to the stern below the envelope. The keel elements had a triangular cross-section; a rigid bow frame and a tail structure, both made in metal elements, reinforced these crucial parts of the craft; the airship had a “cruciform empennage”, with two elevators to control pitch and one rudder. The total length of the ship was 106 meters, its width 26 m, the volume was 18.500 cube meters.

The central keel was also the main connecting element for the three Maybach IV, 245 Hp engines, and for the gondola. The airship structure was made of steel and aluminum elements, connected by weldings and joints which ensured the appropriate compromise between rigidity and elasticity under the often strong dynamic stresses of the flight.

The rear engine cabin

The structure of the keel

The rigid bow frame

An airship lighter than air

Lifting force was mostly provided by the highly flamable hydrogen in the gas chambers of the envelope; the overall mass of dislocated air would cause the airship to float in the air – that is why dirigibles, like balloons, are called “lighter than air” crafts. However, within certain limits and in particular conditions, the airship could also develop some dynamic lift by pulling its nose up during navigation; this would have helped it to keep or even gain altitude like a normal airplane.

Wind and speed

The airship could normally cruise between 80 and 100 km/h (43 and 54 knots) with a top speed of 115 km/h, i.e. 62 knots). The usual cruise was between 80 and 90 km/h of airspeed and was on two engines with the third one stopped. Typically, the operating engines were the central, rear, one and one of the laterals, chosen depending on conditions to achieve some correction of predominant wind-induced lateral drift. The ground-speed, that is the actual movement of the airship relative to the ground, pack or sea, was highly affected by the intensity of wind.

With a 40 km/h headwind and a 90 km/h airspeed, the airship was actually progressing 50 km/h. If the same wind was, instead, blowing into the machine’s tail, then the overall progress was 130 km/h. Evidently, this factor was important and had to be carefully monitored, in long-haul navigations for fuel management reasons. The airship had an overall endurance of 4 to 5 days in powered flight, which is what was needed for the Polar crossing, plus a small safety margin. Fuel onboard was stored in aluminum tanks, attached in pairs to the side beams of the keel, and distributed along the entire length of the airship: this way, while the gasoline was being consumed more or less equally from all tanks, no variation in weight-balance occurred.

Preparetion for departure

Before every flight, the airship had to be thoroughly checked, loaded with the appropriate amount of hydrogen gas, gasoline and lubricant. Weights had to correctly be calculated and distributed in the gondola and keel. Particularly for long flights in remote areas, weights on board were to be carefully limited.

During the Polar crossing, there were 16 people on board the NORGE:

- 8 Norwegians,

- 1 American,

- 6 Italians,

- 1 Swede.

Popular history likes to remember that there was also a 17th crew-member: Titina, a small dog that had been adopted by airship commander Umberto Nobile and accompanied the expedition from the beginning to the end.